The history of Svalbard in a nutshell: from whaling to tourism. The written history of Svalbard begins at the end of the 16th century when Dutch seafarer Willem Barentsz discovered the islands.

Spitsbergen or Svalbard

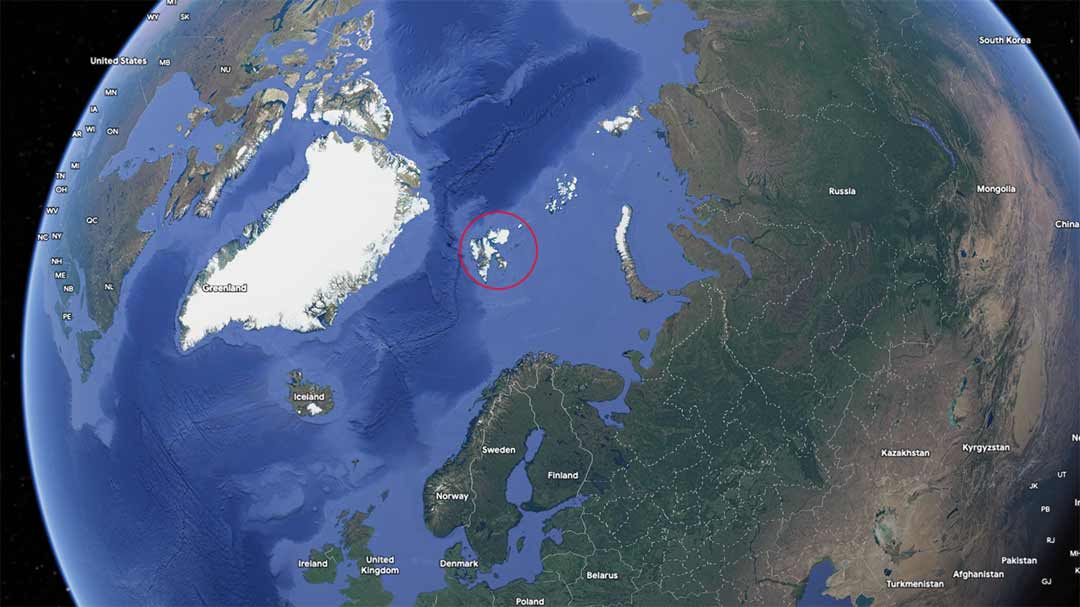

Svalbard is an archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, some 565 km north of Norway and less than 1,000 km from the North Pole, consisting of several larger and dozens of smaller islands. Spitsbergen is the largest island where Longyearbyen is situated, the only town in the archipelago. Sometimes the entire archipelago is referred to as Spitsbergen, but the official name has been Svalbard since 1925.

Willem Barentsz

In 1596, Dutch seafarer Willem Barentsz began his third expedition in search of the northern route to East Asia. During this dramatic last voyage of Barentsz, he first discovered present-day Bjørnøya (Bear Island) and subsequently the archipelago he named after the pointed mountain peaks that stood out against the sky above these rugged shores: Spitsbergen.

Barentsz’s voyage with his ship Witte Swaen (White Swan) took him further east as he set out to explore the seas between Svalbard and Nova Zembla. In the northern part of Nova Zembla, the ship got stuck in the ice. From the wood of their own ship, they built a house known as Het Behouden Huys (The Save House). This is where Barentsz and his crew spent the winter under miserable conditions. In the spring, they built a sloop with which the seventeen survivors returned to civilization. Willem Barentsz died a week after departure. After all the hardships, only 12 sailors would return to Holland.

The cold coast of Svalbard

The name Svalbard was not given to the archipelago until 1925. An Icelandic text from the 12th century mentions a land to the north called Svalbard (Cold Coast). It cannot be ruled out that the archipelago had been discovered before Barentsz, perhaps by the travel-loving Vikings, but no evidence of this has ever been found. There is also no evidence that the “cold coast” actually meant Svalbard. It is more likely that it referred to the island of Jan Mayen, which lies between Iceland and Svalbard.

The ice edge above 80° north latitude.

Whalers and trappers

The waters around Svalbard were rich in whales. In the seventeenth century, it was mainly Dutch and English whalers who hunted whales in the fjords and seas of the archipelago. The Dutch Noordsche Compagnie had whale oil distilleries at Smeerenburg on the island of Amsterdamøya during the fishing season. Many names on present-day Svalbard still remind us of the Dutch influence on this region centuries ago.

By the middle of the 18th century, the Dutch and British lost interest in Svalbard, as virtually all the whales around the island had been killed. Now it was the turn of the trappers to continue the hunt for the animals of Svalbard. The first trappers were the Pomorians from Russia, followed by Norwegian hunters who focused primarily on polar bears. Because trappers were mostly loners living in small huts scattered across the islands, they did not have the same dramatic consequences as whaling.

Coal

In the late 19th century, interest in Svalbard was revived and the archipelago became a popular study area for geographers and geologists. It soon became clear that Svalbard had a large deposit of coal, and the first coal mines were opened in the area. Coal mining continued for a long time until it became unprofitable around 2010. One coal mine is still in operation today, Mine 7. A large part of the production is exported to Germany for the automotive industry.

Svalbard Treaty

Until the signing of the Svalbard Treaty in 1920, the archipelago did not really belong to anyone. It was placed under the supervision of Norway, but with a special status. Taxes are regulated in a different way than in Norway, as there are hardly any social services in Svalbard. It is a land where you have to be able to take care of yourself. No babies may be born there, nor may one be buried there. No visa is required to work in Svalbard. However, there are strict passport controls to enter the country, as it is not part of the Schengen area.

Settlements

In addition to Longyearbyen, there are a number of settlements on Svalbard. Barentsburg with a Russian population of about 500, the coal-mining village of Sveagruve with a population of about 230, the international research station at Ny-Ålesund, and Pyramiden with a population of only 22. Dutch tv maker Floortje Dressing visited Pyramiden in her show “Floortje naar het einde van de wereld“.

Tourism, Research, and Education

The first tourists visited Svalbard as early as the early 20th century, touring the coast in comfortable cruise ships. After 1990, when the coal mining industry was past its peak, tourism really started to take off. It is now one of the main sources of income.

In addition, research and education have also become increasingly important. Students from all over the world come to study at the University of Svalbard (UNIS) that focuses on Arctic research in biology, geology, geophysics and technology.

The future of Svalbard

Climate change is causing Svalbard to warm up six times faster than the global average, with potentially catastrophic consequences for the wildlife and the natural environment. There is no shortage of disturbing phenomena such as retreating glaciers, reduced snow cover, extreme precipitation, disappearing sea ice, avalanches, endangered flora and fauna.

The problems of this region are discussed in Norway. On board our ship was a group of Norwegians with influential positions in the public and private sectors, including a number of parliamentarians, to discuss the various issues. These include balancing economic and environmental interests. The growth of tourism in turn brings with it environmental pollution.

Almost all studies show that the future of Svalbard will be warmer, with less sea ice, fewer polar bears and more rain. Time will tell how this unique region will change in the future and how the flora and fauna will be able to adapt to the new conditions.